Red Sea Conflict Threatens Key Internet Cables

Maritime attacks complicate repairs on underwater cables that carry the world’s web traffic

Article by Drew Fitzgerald

Full Story here: Wall Street Journal

March 3, 2024

Conflict in the Middle East is drawing fresh attention to one of the internet’s deepest vulnerabilities: the Red Sea.

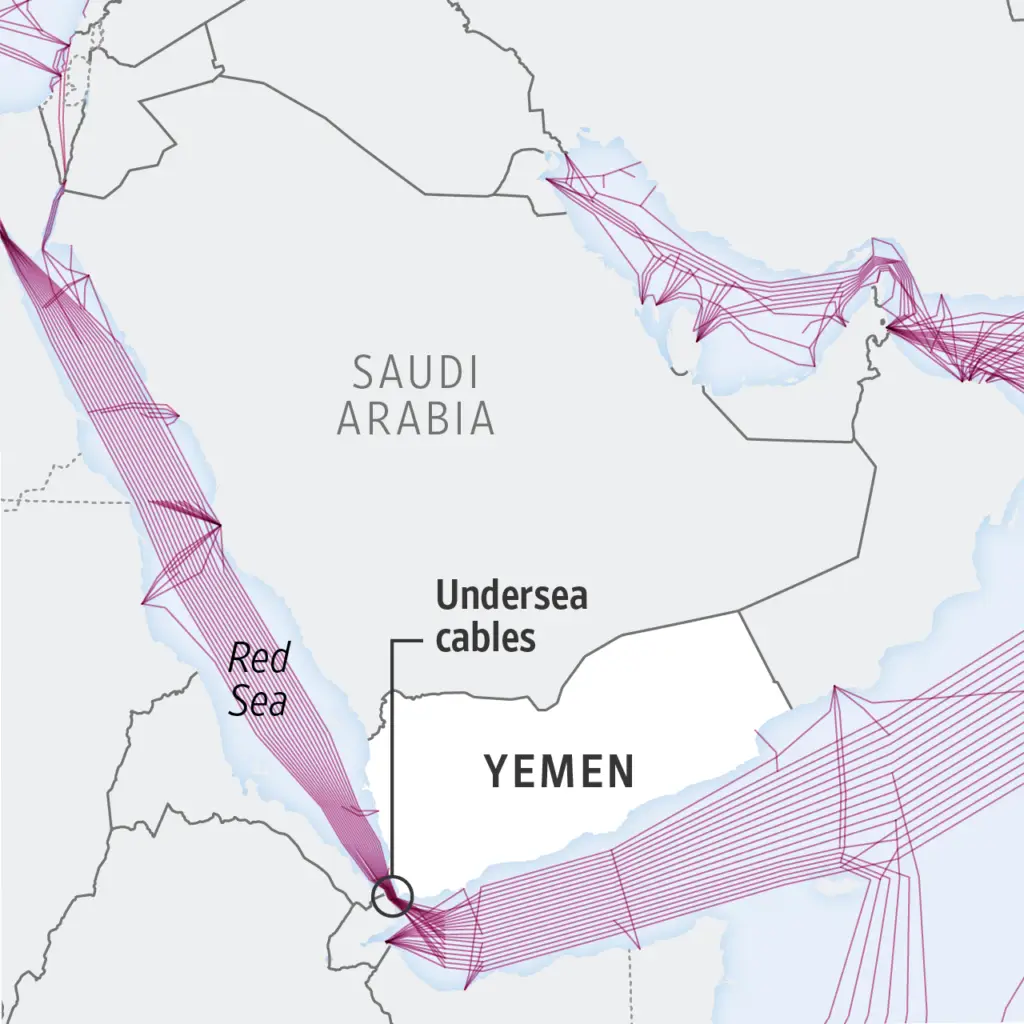

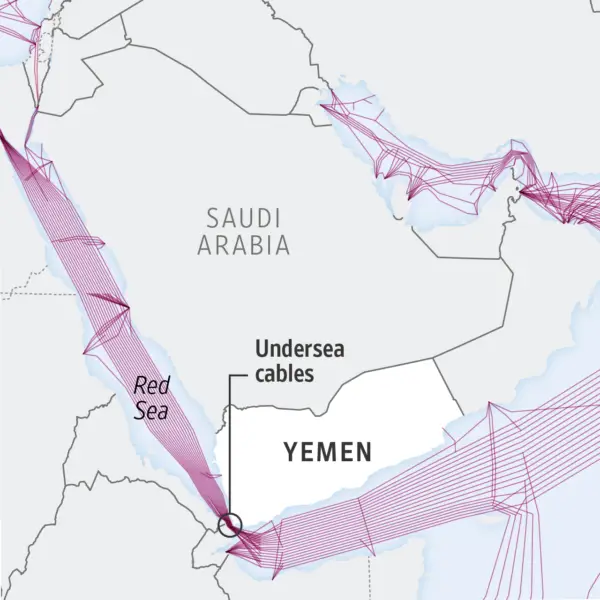

Most internet traffic between Europe and East Asia runs through undersea cables that funnel into the narrow strait at the southern end of the Red Sea. That chokepoint has long posed risks for telecom infrastructure because of its busy ship traffic, which raises the likelihood of an accidental anchor drop striking a cable. Attacks by Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen have made the area more dangerous.

The latest warning sign came Feb. 24, when three submarine internet cables running through the region suddenly dropped service in some of their markets. The cuts weren’t enough to disconnect any country but instantly worsened web service in India, Pakistan and parts of East Africa, said Doug Madory, director of internet analysis at network research firm Kentik.

It wasn’t immediately clear what caused the cutoffs. Some telecom experts pointed to the cargo ship Rubymar, which was abandoned by its crew after it came under Houthi attack on Feb. 18. The disabled ship had been drifting in the area for more than a week even after it dropped its anchor. It later sank.

Yemen’s Houthi-backed telecom ministry in San’a issued a statement denying responsibility for the submarine cable failures and repeating the government is “keen to keep all submarine telecom cables…away from any possible risks.” The ministry didn’t comment on the Rubymar attack.

Mauritius-based cable owner Seacom, which owns one of the damaged lines, said fixing it will demand “a fair amount of logistics coordination.” Its head of marketing, Claudia Ferro, said repairs should start early in the second quarter, though complications from permitting, regional unrest and weather conditions could move that timeline.

“Our team thinks it is plausible that it could have been affected by anchor damage, but this has not been confirmed yet,” Ferro said.

Cable ships’ lumbering speed makes draping new lines near contested waters a dangerous and expensive task. The cost to insure some cable ships near Yemen surged earlier this year to as much as $150,000 a day, according to people familiar with the matter.

Yemen’s nearly decadelong civil war further complicates matters. Houthi rebels control much of the western portion of the country along the Red Sea, while the country’s internationally recognized government holds the east. Companies building cables in the region have sought licenses from regulators on both sides of the conflict to avoid antagonizing either authority, other people familiar with the matter say.

The mounting cost of doing business also threatens tech giants’ efforts to expand the internet. The Google-backed Blue Raman system and Facebook’s 2Africa cable both pass through the region and remain under construction. Two more telecom company-backed projects also are scheduled to build lines through the Red Sea.

Most of the internet’s intercontinental data traffic moves by sea, according to network research firm TeleGeography. Submarine cables can be simpler and less expensive to build than overland routes, but going underwater comes with its own risks. Cable operators report about 150 service faults a year mostly caused by accidental damage from fishing and anchor dragging, according to the International Cable Protection Committee, a U.K.-based industry group.

“Having alternative paths around congested areas such as the Red Sea has always been important, though perhaps magnified in times of conflict,” ICPC general manager Ryan Wopschall said.

Several internet companies have considered ways to diversify their connections between Europe, Africa and Asia. Routes across Saudi Arabia, for instance, could skirt the waters around Yemen altogether. But many national regulators charge high fees or impose other hurdles that make sticking to tried-and-true routes more attractive.

“The industry, as with any industry, reacts to the conditions set upon it, and routing in Yemen waters is a result of this,” Wopschall said.

Benoit Faucon contributed to this article.

Write to Drew FitzGerald at [email protected]

Latest News & Updates

Stay informed with the latest press releases, industry news, and more.